Let's Do The Time Warp ... and Weft

You really can't transcend your own time.

- Melinda Hartwig, PhD, curator, Michael C. Carlos Museum

I recently attended a fascinating lecture on antiquities. The most interesting part was about forgery. The lecturer explained how, after some critical accumulation of time and knowledge, a fake is revealed. Something shifts, and a curator sees with new eyes. "Not Byzantine, Victorian! That sculpture is not what it's pretending to be."

That made me think about costumes and historical-reproduction clothing. About how no matter how hard we try to recreate the fashions of the past, something always gives us away. The sartorially savvy will, almost without exception, realize the garment is not what it's pretending to be.

Sometimes, a designer may not have been trying to recreate history at all. The "forgery" was never meant to fool anyone. Perhaps the intent was to capture the spirit of the time. Take the most recent film iteration of Anna Karenina:

Durran's version of the 1870s.

Durran's version of the 1870s.

Costume designer Jacqueline Durran has said in interviews that her version of 1870s bustle dresses was influenced as much by the architectural silhouettes of 1950s couture (Charles James et al.) as by Victorian fashion. Historical accuracy was never her intention.

Below are original 1870s ball gowns for comparison. Compare the fabrics, embellishments, and overriding symmetry with Durran's Oscar-winning costumes.

In other striking departures from historicity, the costumer's primary concern may have been wooing the audience or showcasing a star's assets:

Anne Baxter and Debra Paget wear Edith Head's Oscar-winning designs.

Edith Head was not attempting to replicate biblical-era dress with her designs for The Ten Commandments (1956). Her aggressively mid-century looks were surely meant to appeal to contemporary moviegoers.

I argue that by emphasizing body parts (waist, bust) and styling (red lips, sculpted hair) currently en vogue, Head was intentionally creating a more-relatable ancient Egypt. It's a very (very) long movie and theater-goers hadn't signed up for a documentary. Furthermore, Academy Awards are not bestowed by museums or historians.

Examples of costume designers playing fast and loose with history -- for any variety of reasons -- abound. Whether it's always a conscious decision on their part is up for debate.

Take Walter Plunkett's beloved 1939 costumes for Gone With the Wind.

Scarlett O'Hara's dress is only marginally more historically accurate

Scarlett O'Hara's dress is only marginally more historically accurate

than the one Carol Burnett wears in her hilarious spoof.

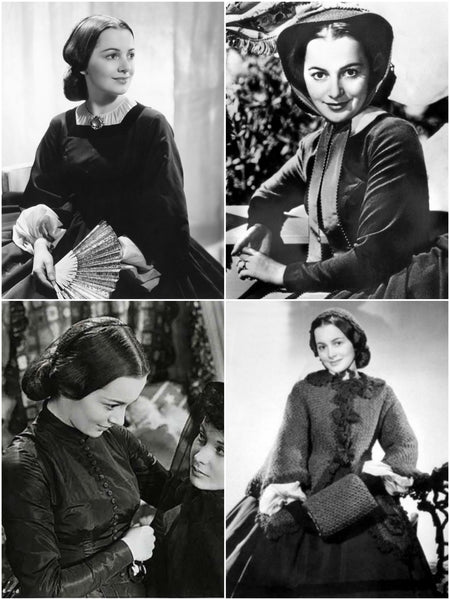

Only Olivia de Havilland's garments and styling as Melanie Hamilton Wilkes came close to resembling the actual fashions and styling of the 1860s.

Even if you'd never seen either film, would you have any difficulty determining which pair of star-crossed lovers is from 1936 and which is from 1968? I don't think the filmmakers necessarily intended their Romeo and Juliet to appear firmly rooted in their modern decade. Yet, they do.

Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer (1936)

vs.

Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey (1968)

A vintage-loving friend recently mentioned being irked by Ralphie's mom's oh-so-80s hairdo in "A Christmas Story." The film is from 1983. And you can tell.

Melinda Dillon's big 80s hair is out of place in this 1950s scene.

Despite the Edwardian underpinnings, this dreamy opening scene from the original Picnic at Hanging Rock immediately declares its mid-1970s production:

These Marcia Brady look-alikes may be lacing corsets, but they could just as easily be teaching the world to sing in perfect harmony.

These Marcia Brady look-alikes may be lacing corsets, but they could just as easily be teaching the world to sing in perfect harmony.

In contrast, some of the most convincing work I've seen were Ms. Durran's Oscar-nominated designs for Mr. Turner (2015). Rumpled and detailed just so, these clothes had the magical effect of blending into the scene. I realized halfway through the film that I wasn't noticing the "costumes" but simply enjoying each character's clothing.

Those familiar with romantic era construction would surely recognize these as costumes, not antiques, if they viewed them up close. What wardrobe department can hand-stitch the thousands of garments needed for a large-scale production? But the on-screen effect was marvelously authentic.

When Durran goes for historical accuracy, she nails it. It's interesting that her Oscar win was for the objectively less-authentic designs.

Hollywood values creativity over accuracy, which is fine. If we're talking about movies (documentaries aside), they're purely entertainment. It's hardly criminal for an actor's styling to miss the historical mark.

That's artistic license, budget limitations, and/or nods to current fashion at work (if we assume knowledge of historic dress on the part of the designer). If the audience collectively sighs "aah!" and the costumes enhance the story, it's a job well done. We can make fun of historical inaccuracies, but it's hard to argue an ethical crisis.

But what if it's an unscrupulous or under-educated seller claiming something is older than it actually is or concealing their lack of knowledge? What if it's an educator, museum docent, or historical re-enactor imparting misinformation? Do they have a moral imperative to know what they're selling or describing, or, at minimum, to disclose a lack of knowledge? I think so.

I made this dress using a real 1930s pattern. The ingredients are modern (I didn't trust my fledgling skills with expensive fabric). But even if I'd used high-quality vintage materials, would it fool an expert on close inspection? I doubt it. Could I sell it on eBay as a 30s original? Probably.

Another example is this hat and purse set I crocheted from a vintage pattern using vintage yarn. There's nothing tangible to give the finished products away as new. There's no difference between crochet stitches then and now. Again, I could rough these up a bit and sell them as vintage.

But are they vintage? No. These newly created pieces haven't "lived through" the interim and somehow, that makes a difference. Their newness isn't merely conceptual or a matter of semantics. Somehow, you can feel it. Both literally and figuratively.

For stage or screen, passing off new as old can be a worthy undertaking. But for sellers? If you don't disclose the full story, you're being dishonest. Misleading someone -- even by omission, and even if they're happy with the item or the information they've received -- is unethical.

In a follow-up post I'll discuss how to recognize a "forgery," even if it's a really old one. For now, what play, movie, TV show, or other production set in the past do you find most, or least, authentic? Have you ever been sold something antique or vintage, only to discover it was newer than advertised?

Click here to read about the world's most-famous forgery. Or is it?

Click here to do The Time Warp again.

Comments

Oh, there are soooo many badly costumed historical movies out there (just head over to FrockFlicks…). Some I can tolerate, some I can’t. But yes, some designers do really nail it. The Turner pic was great. As much slapstick there is in them, what really stunned me on watching them again where the Three Musketeers/Four Musketeers movies by Richard Lester. Just blank out Ms. Welch, and there are a few things that Faye Dunaway wears that are probably a bit fanciful, but otherwise, it looks really, really good and most of all – they don’t look like 70s movies.

Great post, Liza!

Impressive blog. Thanks for the share.

I costume 19th c. dolls, Some of them having a hammer price of 300,000.00. My mentor [ fashion historian and seamstress ] steered me way out of the box to that elusive classroom named authentic. Drown yourself in crumbling textiles, but make notes about construction, drape, ruching and pleating as you descend into the vortex of mediocrity, Hold your breath and the sweet air of truth will carry you to the surface, There is alot I could say, but the polite lies are wrapped like petals of a flower, even to the point of copying European accent with all its premeditated charming errors, So, I found myself here,

Hi, Michelle. Not sure I follow, but I thank you for taking the time to read the blog and leave a comment!